“The Stability Pact needs to be reformed. Increasing the debt limit in euros would make economic sense. The economic environment has changed. “Permanently lower interest rates change a lot of things.” This was stated, among others, by the head of the ESM, Klaus Regling, in an interview with the German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Maastricht Treaty.

On 7 February 30 years ago, the Maastricht Treaty was signed, bringing the euro into existence. What was your experience at the time?

Klaus Regling: I had just returned to the Federal Finance Ministry from the International Monetary Fund in Indonesia. Shortly after, the preparations for the euro began. No one knew whether it would work.

The Germans in particular were sceptical. Bundesbank head Karl Otto Pöhl called a central banker and asked, “Do you know what those idiots are doing?”

I have never heard that before. Pöhl was there from the beginning. He sat on the Delors committee, which put forward proposals for the euro. He made sure that the European Central Bank would become independent from governments. That was very important, because more than half of the European central banks were not independent at that time.

When the euro plans got underway, the European Monetary System (EMS) began to wobble…

That was one of the many crises that no one remembers today. In 1992, the British and Italians left the EMS. In 1995 came the next crisis, when Italy’s lira depreciated by about 20 per cent against the Deutschmark in the spring. That was good for me as a tourist, but bad for the German industry. It cost one per cent of Germany’s economic growth. People always remember the crises of the euro. But before the euro there were many more crises! A disruption of one of the major currencies upset Europe’s internal market every time. Only with the euro could the internal market show its full benefits. German exporters in particular have benefited from this.

But you do not want to claim that things always went as you had imagined with the euro, do you?

No. In the 1990s, the entry criteria for the euro forced governments to have similar economic policies. The budget deficit had to be below 3%, inflation had to be tamed, otherwise a country did not get into the euro. That was good…

…but it did not stop there.

It was disappointing that after the start of the euro, in 1999, countries relaxed their policies. Greece’s high budget deficits are well known. It also became problematic that several countries lost competitiveness. Incomes rose too much in the first euro decade in relation to countries’ output. That was the reason for the euro crisis from 2010 onwards. There were macroeconomic imbalances that had to be corrected. Even if that meant painful cuts.

When did you think: now the euro will fail?

Never. But there was a time when it looked like individual countries could have to leave the euro area, such as Greece. In the beginning, even more countries were at risk.

In 2015, the then German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble pushed for Greece to be thrown out. Why did you oppose that?

We never argued personally. I respect his reasons. He wanted to force euro countries to take economic policy discipline seriously, which participation in the monetary union requires. But I thought the cost to the Greeks was too high. Their incomes had already fallen by a quarter. That was in large part necessary to reduce the imbalances. But there were calculations that a euro exit would cut their incomes by another quarter. That would have led to even more severe social problems. Moreover, a Greek exit from the euro would have changed the nature of the monetary union.

But do not we really need more pressure for states to reduce debt in good times? Governments have often not taken the Stability Pact seriously.

The Stability Pact has worked better than claimed. In 2019, only one euro area country had a deficit of just over 3%. At the end of the economic boom, the US, Japan and the UK had much higher deficits than the euro area.

Debt swelled as a result of the Corona crisis and is in some cases higher than before the outbreak of the euro crisis ten years ago.

But there is one central difference: now, no country could do anything to prevent the pandemic. Ten years ago, by contrast, the financial markets distrusted some euro area countries because they had major economic problems. A lot has changed since then. The ESM only granted loans against reforms, and the countries carried them out. Greece had a “black zero” in its budget from 2016…

…and now has debts of 200% of its economic output.

But only because, like other countries, it spent money to control the pandemic. That was absolutely the right thing to do, otherwise the economic collapse in 2020 would have been much more severe. Economists, who do not typically agree on much, agree on that. The euro is doing well despite increased debt. Financial markets see that the debt piles in the US, the UK, and Japan have increased much more than in the euro area.

But if the European Central Bank raises interest rates because of inflation, it will be tight for highly indebted euro area countries, won’t it?

No. A country or an individual is not threatened with bankruptcy because its debts reach a certain level, but because it cannot bear the interest burden. Thirty years ago, Italy spent almost 12% of its economic output on interest payments. Today it is less than 3.5% because of the fall in interest rates. Interest rates will rise, but not so much that it will become difficult for Italy, or others, in the foreseeable future.

Savers will still not get reasonable interest on their bank accounts in the future. But what makes you so sure?

The economic environment has changed. The main reason for today’s low interest rates is not central banks. It’s because ageing societies are saving more, and at the same time less has been invested in recent years. A lot of money on offer and less demand are causing interest rates to fall. The high savings rate, which has also risen due to increasing inequality in wealth distribution, will not fall any time soon. By the way, this is not a European phenomenon: the global interest rate is lower than it was twenty or thirty years ago, allowing for higher public debt levels without the country being threatened with insolvency.

So, you are completely relaxed about debt piles like Italy’s…

No. It is clear that euro area countries with above-average debts have to act. The ageing of society will also require higher spending on pensions and healthcare in the future. Besides, there will always be crises. And then each government should have leeway for higher spending.

Will the euro survive the next crisis?

The euro is much more crisis-proof today thanks to the ESM and other institutions that were built up recently. But we should do more. For example, complete banking union and capital markets union…

…which is EU jargon for projects, as ambitious as they are tough, to create a common and harmonised market for the banking sector and stock exchange transactions.

Correct! We have 19 national capital markets in the euro area. An investor from Asia needs a separate tax lawyer for each country. That is not particularly attractive. A common capital market would be good for investors, companies, savers, and therefore also for growth. And for some time, another idea has been around on how the euro could become less vulnerable: The euro area needs a permanent stability fund to prevent full-blown crises. Governments in a recession would get cheap loans from it quickly and easily. For example, it could be stipulated that states can access it if their unemployment rate rises significantly above the long-term average or their growth slumps by a certain percentage. That would make the euro area even more robust.

And who is going to pay for that?

This is not about a new budget. The governments would pay back the loans in the next economic upswing.

Who grants the loans?

My suggestion would be that the ESM could do this quite well. We are collecting enough money on the financial markets at low interest rates anyway. But other models are also conceivable.

The EU is currently discussing whether the Stability Pact should in the future allow a debt level of, for example, 100 instead of the current 60% of gross domestic product. Would not that be dangerous?

No. The Stability Pact must be reformed. Raising the euro debt threshold would make economic sense. The economic environment has changed. The permanently lower interest rates change many things. Because of low interest rates, debt levels can be higher than was thought at the time of the Maastricht negotiations 30 years ago. If the European Commission continues to demand that some governments need to aim for the 60%, this is not only politically difficult, it could also choke off growth. Demanding something painful that is economically unnecessary will ultimately not succeed. Whether the new target should be exactly 90 or 100 or 105% cannot be derived scientifically. That is a political decision.

Another proposal is to soften the 3% upper limit for the annual budget deficit. Investments to combat climate change could be excluded. Would that be good?

The Stability Pact is supposed to guarantee the sustainability of public debt. Green investments also increase the debt level, and we simply have to be careful with that. That is why the 3% ceiling should continue to apply in principle. In individual cases, however, governments should be allowed to exceed it if the European Commission comes to the conclusion that there really is an investment gap, and that closing that gap would boost growth, while not putting debt sustainability at risk.

Will the euro ever be as important as the dollar?

We can certainly catch up, even if the dollar is likely to remain the number one reserve currency. One goal would be to develop a multipolar currency system, with the dollar, the euro and the Chinese renminbi. Europe should get on with it. China has recently achieved astonishing successes with its currency. If we are not careful, we will soon end up in third place.

Latest News

Greek €200M 10Y Bond to be Issued on April 16

The 3.875% fixed-interest-rate bond matures on March 12, 2029, and will be issued in dematerialized form. According to PDMA, the goal of the re-issuance is to meet investor demand and to enhance liquidity in the secondary bond market.

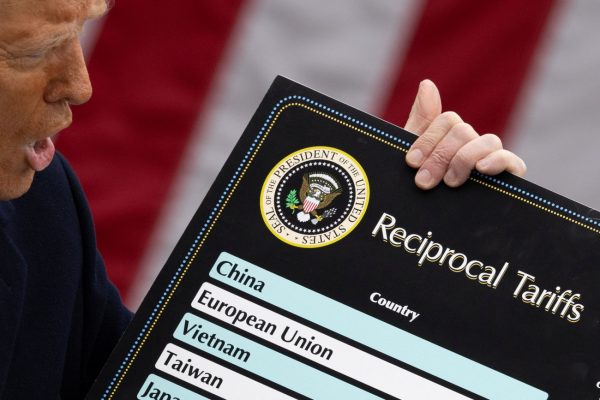

German Ambassador to Greece Talks Ukraine, Rise of Far Right & Tariffs at Delphi Economic Forum X

Commenting on the political developments in his country, the German Ambassador stressed that it was clear the rapid formation of a new government was imperative, as the expectations across Europe showed.

Athens to Return Confiscated License Plates Ahead of Easter Holiday

Cases involving court orders will also be excluded from this measure.

Servicers: How More Properties Could Enter the Greek Market

Buying or renting a home is out of reach for many in Greece. Servicers propose faster processes and incentives to boost property supply and ease the housing crisis.

Greek Easter 2025: Price Hikes on Lamb, Eggs & Sweets

According to the Greek Consumers’ Institute, hosting an Easter dinner for eight now costs approximately €361.95 — an increase of €11 compared to 2024.

FM Gerapetritis Calls for Unified EU Response to Global Crises at EU Council

"Europe is navigating through unprecedented crises — wars, humanitarian disasters, climate emergencies," he stated.

Holy Week Store Hours in Greece

Retail stores across Greece are now operating on extended holiday hours for Holy Week, following their Sunday opening on April 13. The move aims to accommodate consumers ahead of Easter, but merchants remain cautious amid sluggish market activity.

Green Getaway Ideas for Easter 2025 in Greece

Celebrate Easter 2025 in Greece the sustainable way with eco-farms, car-free islands, and family-friendly getaways rooted in nature and tradition.

Civil Protection Minister Details Summer Firefighting Plans at Delphi Forum

At the 10th Delphi Economic Forum, Minister of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection Yiannis Kefalogiannis discussed Greece's plans for the upcoming fire season.

How Shops and Markets Will Operate During Easter Holy Week

The Easter holiday schedule has been in effect since April 10, with retail stores open Palm Sunday, and most supermarkets also operating to meet consumer demand for Easter shopping

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης