“Europe is facing one of the its toughest winters” pointed out Mr Evangelos Marinakis, chairman and founder of Capital Maritime & Trading Corp., as he began his speech at the Economist conference in Thessaloniki where he participated in a panel with Paolo Scaroni, deputy chairman of the Rothschild Group, chairman of Milan and former CEO of ENI.

It is the question of how Europe will be able to cover the real energy deficit it faces due to the interruption of Russian gas flows, a deficit that will be even more acute if this winter proves severe, while they also discussed the risk that the measures taken to deal with the energy crisis will ultimately be a setback in terms of decarbonisation and green transition.

And a panel attended by the chairman of a leading Greek shipping group – currently leading the way in LNG transportation and the transition to green shipping – and the former CEO of an energy giant and now a leading executive of a global financial group, proved to be the right forum to have this discussion.

Evangelos Marinakis’ speech:

Europe is facing one of its toughest winters.The War in Ukraine has been the catalyst that has helped us realize the challenges that we are facing:

-challenges that have to do with collective security, peace and stability and how to deal with the fact that because of Russian aggression, Europe is becoming a theatre of war,

– challenges that have to do with avoiding conditions of energy poverty and social crisis.

– and challenges that have to do with becoming less dependent upon fossil fuels.

And it is true that Europe has shown a lack of preparedness: both in relation to having a strategy to avert aggression and war and in relation to dealing with possible energy crises.

But I do think that Europe can still stand up to the challenges.

Take energy for example. There has been a tremendous effort to replace Russian gas with LNG, after we realized that pipelines from a single provider were becoming a liability, a trap.

That is why we have tried to help as much as possible with the transportation of LNG, even before the disruption of the supply of natural gas caused by the war.

Shipping offers a reliable, flexible and efficient way to transport LNG wherever this is needed and without the geopolitical, technical and environmental problems of large-scale pipeline projects.

And we are proud that Greek shipping is today a leading force in the transportation of LNG.

Almost one out of six LNG carriers being built in the world today will be delivered to Greek shipowners.

Total investment in building new LNGCs by Greek ship-owners is approximately $30 billion, 160 ships in total, a massive investment.

Capital invested more than $3.2 billion in LNGCs over the last four years.

This is how serious we take working towards reducing Europe’s dependence on a single supplier and this is how we enable Europe’s answer to the current energy blackmail by Russia.

Increased investment in LNG infrastructure in Europe is today –and until a new wave of renewable energy projects is in place – the only solution to have a less energy-dependent Europe.

And at the same time this is a step towards a greener future, because we all know that natural gas is the crucial ‘transition fuel’ in any serious effort to decarbonize.

Investing in LNG infrastructure is now a much better solution than returning to increased use of coal and lignite, fossil fuels with significantly worse environmental impact.

But of course the challenge of Green transition is not limited to increased use of natural gas.

The easiest thing would be to come here and say: Shipping is not the biggest contributor to climate change and global warming. It only contributes 3% of greenhouse gases even though it is responsible for 80% of global transport.

But in shipping we do care about climate change.

In particular in Greek shipping!

After all when discussing climate change we are not talking about the distant future.

We are talking about large segments of the planet being uninhabitable by 2050, unless we take urgent action today.

We are talking about areas – including small island nations – being covered by water.

We are talking about mass climate migration.

We are talking of large disruptions in agriculture.

We are talking a global crisis, the biggest that humanity has faced in modernity

Greece is in a position to contribute significantly to climate change as it controls the largest commercial fleet in the world including:

34% of the world oil tanker fleet

24% of the world bulk carriers

19% of the world Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) carriers

19% of the world chemical & product tankers

11% of the world Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) carriers

8% of the world containerships

But with great size also comes great responsibility

There are many in the shipping industry that basically just want to ‘buy more time’. Get more exceptions for shipping. Postpone the transition to Green Shipping.

We should go the opposite direction.

Accelerate the Green Revolution that Shipping needs.

By increased research on low to zero-carbon fuels, from biofuel-blended marine fuel to the research on ammonia fuel cells.

By increased investment in exhaust cleaning systems and all forms of sustainable shipping.

By making sustainability an integral part of shipping.

In Capital we have taken all possible steps to be part of the Green Revolution in Shipping:

– Capital is currently participating in a major European Commission Research shipping project, ShipFC, examining the conversion of an offshore vessel to run on ammonia-powered fuel cell.

– Capital and Lloyd’s Register (LR) trial the use of biofuels in a new pilot project to support the maritime industry’s research for low to zero-carbon fuels in line with the IMO’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets. The trial will test biofuel-blended marine fuel on Capital managed 300k DWT crude tanker, Apollonas.

– Capital participates in a group of leading companies in maritime transportation investigating the realities of using ammonia (NH3) as a marine fuel, focused on the safety issues that need to be addressed led by Bureau Veritas Solutions Marine & Offshore.

– Capital is a member of the Clean Shipping Alliance 2020, which aims to support and educate on the use and effectiveness of Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems in order to help achieve shared environmental and sustainability initiatives in the commercial shipping and cruise industries.

These are just some examples that point to how serious we take the challenge of decarbonization and fighting climate change.

And we are willing to invest even more resources to that direction.

However, the transition to Green Shipping is something that needs support and the mobilization of resources. It is important the European Union supports even more this transition by funding research and also funding new investment. It is important that the banking sector prioritizes financing Green Shipping projects. It is imperative that the regulatory framework of global shipping functions as an incentive to move towards sustainable and environmentally friendly forms of shipping. And of course this also creates many high-skill new jobs.

And this is a way for Europe to prove that it can turn its supposed weakness, namely the fact that it lacks fossil fuel reserves that other areas have, into strength.

The future of the globe does not belong to autocracies funding wars by taking advantage on our continuing dependence upon fossil fuels.

It belongs to democracies investing in cleaner greener technologies, accelerating the Green Transition and finding ways to collectively design a sustainable future.

Shipping is at the heart of global trade. It is the complex lifeline that makes sure that goods arrive, that countries can export, that societies can prosper, that people can free themselves from poverty. It is the basic material infrastructure of globalization. It represents the greatest part of the supply chains that sustain our way of life.

And if until now it has been part of the problem of Global Warming and of a pending climate disaster, now it has the chance to be part of the solution!

Paolo Scaroni’s speech

“When I started to prepare my speech for today, a couple of weeks ago, the issue we had to face was whether Europe might have to do without Russian gas, and what we might have to do to prepare for this occasion.

Cutting off the flow of Russian gas just as we were heading into winter seemed to be the worst case scenario. Of course, that is exactly what happened. We are now in a scenario of full economic warfare, in which we will have to do without Russian gas for the foreseeable future.

The question is how. In a world without Russia, will we able to access enough energy? At what price? Will the energy crisis force us to let go of our decarbonization objectives?”

On the first question, Paolo Scaroni did not “mince his words” as to the difficulties we have to face:

“The answer is that over the next 12-24 months things will be tight. Russia accounted for around 150 billion cubic meters of gas, out of the 500 billion cubic meters bcm) of European consumption (I am always giving numbers of the European Union only). How could we substitute all this quantity directly?

LNG is the first candidate and in the EU we have some regasification capacity to be able to receive something around 40-50 bcm.

Secondly, we need to fill up existing import pipelines which means Algeria, Norway and Azerbaijan, and can be calculated at something around 20 bcm.

Thirdly, we have the opportunity to switch fuels so that we consume less gas. Running coal plants at full capacity might reduce demand by roughly 40 billion cubic metres.

None of these are easy to do, and even if we do them all of them together, we could probably be able to replace 110-120 bcm of the 150 bcm of gas we currently import from Russia.

And we should take into account three things. Firstly, demand for gas is highly seasonal, so any shortfall should be concentrated in the winter months. Secondly, we should hope that the coming winter will not be very cold, because a very cold winter would mean 20-30 billion cubic meters in Europe. And thirdly, we should bear in mind that, whatever the shortage, it will bite hardest at those areas that are most reliant on Russian gas – Germany and Eastern Europe.

This will test the concept of solidarity in the EU. Will those who are less dependent on Russian gas take a cut in supply to help those who are more reliant on Russian gas? The next year or two look very challenging, but I think we will manage the situation, as long as we do not have problems with some other suppliers. Let’s hope so.

This talk about a tight market brings me to the second question. What prices should we pay for energy?

As of yesterday gas prices at the TTF, the main trading hub, were around 200 Euros per MWh, more than 10 times higher than used to be. This is a problem for the European continent as a whole; it is also a problem for industry, which is forced to shut down. Initial signs point to a decline of gas use for industrial use between 10 and 20 per cent. Hardly a day goes without a manufacturer announcing that they are suspending production.

It is also a drama for consumers, whose energy bills are rising at a time when inflation is already cutting into what they can afford to buy. No wonder the EU is considering price caps on gas, measures to decouple the price of electricity from that of gas, and big subsidies for industries and consumers.

These may not be “market orthodoxy”, but we are currently in a war economy.

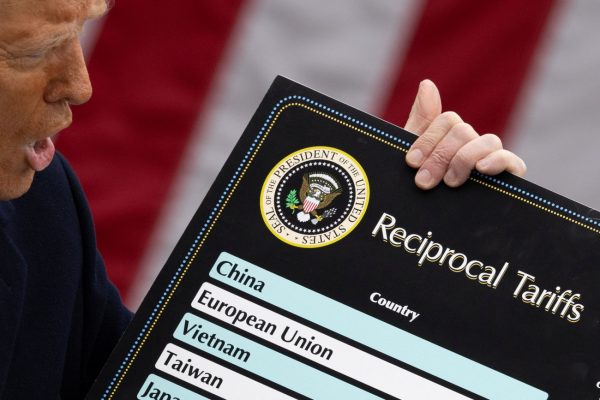

What is perhaps less understood is that even if the situation normalizes, say in the mid 2020s – if Europe increases its LNG import capacity and we solve most of the problems – we will end up with a price for gas 2-3 times higher than the price in the US, and possible twice the price that will be paid in China.

Having high energy costs will be a big issue for the European Union, considering the many energy-intensive companies need to relocate to the US and the Middle East.

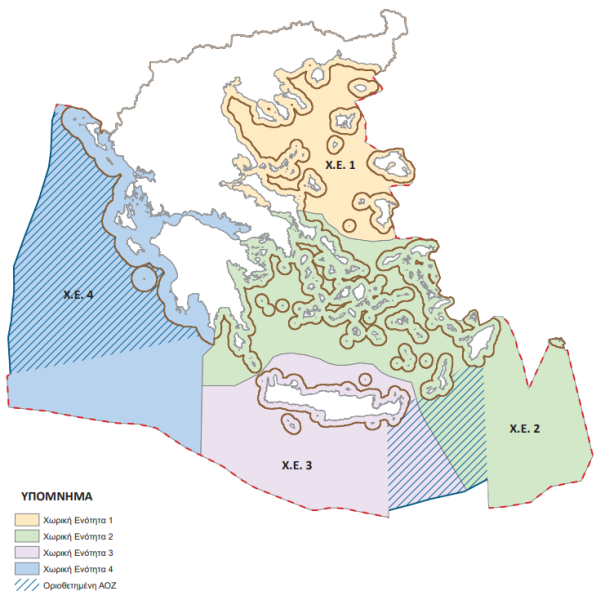

One way of reducing energy prices in Europe would be to increase supply through other pipelines, including maybe Nabucco, the Eastern Mediterranean pipeline. But we would also have to put commercial pressure on producers that are tied to us as we are on them. The list includes North African countries and NATO members, such as Norway, which benefits from the current situation but should extend its solidarity to other NATO members.

Increasing gas supply requires investment in gas production and infrastructure with a payback period of decades, at a time when Europe is trying to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels.

And this brings me to the third question I asked. Will the energy crisis force Europe to let go of its decarbonisation efforts?

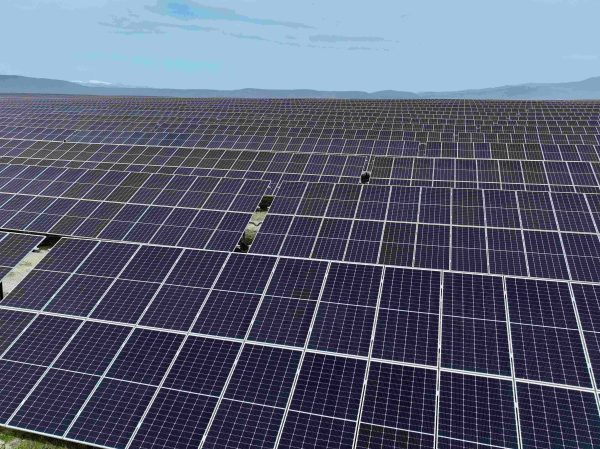

In theory there is an near perfect convergence between decarbonisation and supply security. The more solar panels, wind farms, grids, batteries and electrolyzing we can done, the more we will cut reliance on Russian gas. This suggests that European Union should decarbonize as fast as it can, which is of course true. However, it is not as straightforward as its sounds.

The first point to note is that in the immediate aftermath of the energy crisis we will have actually recarbonized our economy. Coal use in the EU has gone up by 30%. Secondly, accelerating investment in renewables, batteries, grids, hydrogen, etc. requires government money that may be needed to subsidise energy bills. And thirdly, to ensure supply security, we need to provide long-term return visibility for upstream and midstream fossil fuel projects, starting now. And this creates a risk of lock-ins with regard to fossil fuels, which may impair the take-up of renewable energy sources.

That said, I believe that the energy crisis will be a net positive for the EU decarbonisation strategy. As we search for alternative ways to accessing energy, it will force governments and the private sector to think outside the box, which is positive for new nuclear, hydrogen, synthetic methane and carbon capture and storage. These are key pieces of the decarbonisation puzzle, accounting for around half of the energy we will consume in a net zero world.

Going green can also be a way we will overcome our structural disadvantage compared to gas-producing regions of the world. It will be hard for the EU to match the US in gas price, but in a fully decarbonised world there is no reason to believe that our sunlight will be more expensive than theirs.”

Latest News

Greek €200M 10Y Bond to be Issued on April 16

The 3.875% fixed-interest-rate bond matures on March 12, 2029, and will be issued in dematerialized form. According to PDMA, the goal of the re-issuance is to meet investor demand and to enhance liquidity in the secondary bond market.

German Ambassador to Greece Talks Ukraine, Rise of Far Right & Tariffs at Delphi Economic Forum X

Commenting on the political developments in his country, the German Ambassador stressed that it was clear the rapid formation of a new government was imperative, as the expectations across Europe showed.

Athens to Return Confiscated License Plates Ahead of Easter Holiday

Cases involving court orders will also be excluded from this measure.

Servicers: How More Properties Could Enter the Greek Market

Buying or renting a home is out of reach for many in Greece. Servicers propose faster processes and incentives to boost property supply and ease the housing crisis.

Greek Easter 2025: Price Hikes on Lamb, Eggs & Sweets

According to the Greek Consumers’ Institute, hosting an Easter dinner for eight now costs approximately €361.95 — an increase of €11 compared to 2024.

FM Gerapetritis Calls for Unified EU Response to Global Crises at EU Council

"Europe is navigating through unprecedented crises — wars, humanitarian disasters, climate emergencies," he stated.

Holy Week Store Hours in Greece

Retail stores across Greece are now operating on extended holiday hours for Holy Week, following their Sunday opening on April 13. The move aims to accommodate consumers ahead of Easter, but merchants remain cautious amid sluggish market activity.

Green Getaway Ideas for Easter 2025 in Greece

Celebrate Easter 2025 in Greece the sustainable way with eco-farms, car-free islands, and family-friendly getaways rooted in nature and tradition.

Civil Protection Minister Details Summer Firefighting Plans at Delphi Forum

At the 10th Delphi Economic Forum, Minister of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection Yiannis Kefalogiannis discussed Greece's plans for the upcoming fire season.

How Shops and Markets Will Operate During Easter Holy Week

The Easter holiday schedule has been in effect since April 10, with retail stores open Palm Sunday, and most supermarkets also operating to meet consumer demand for Easter shopping

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης