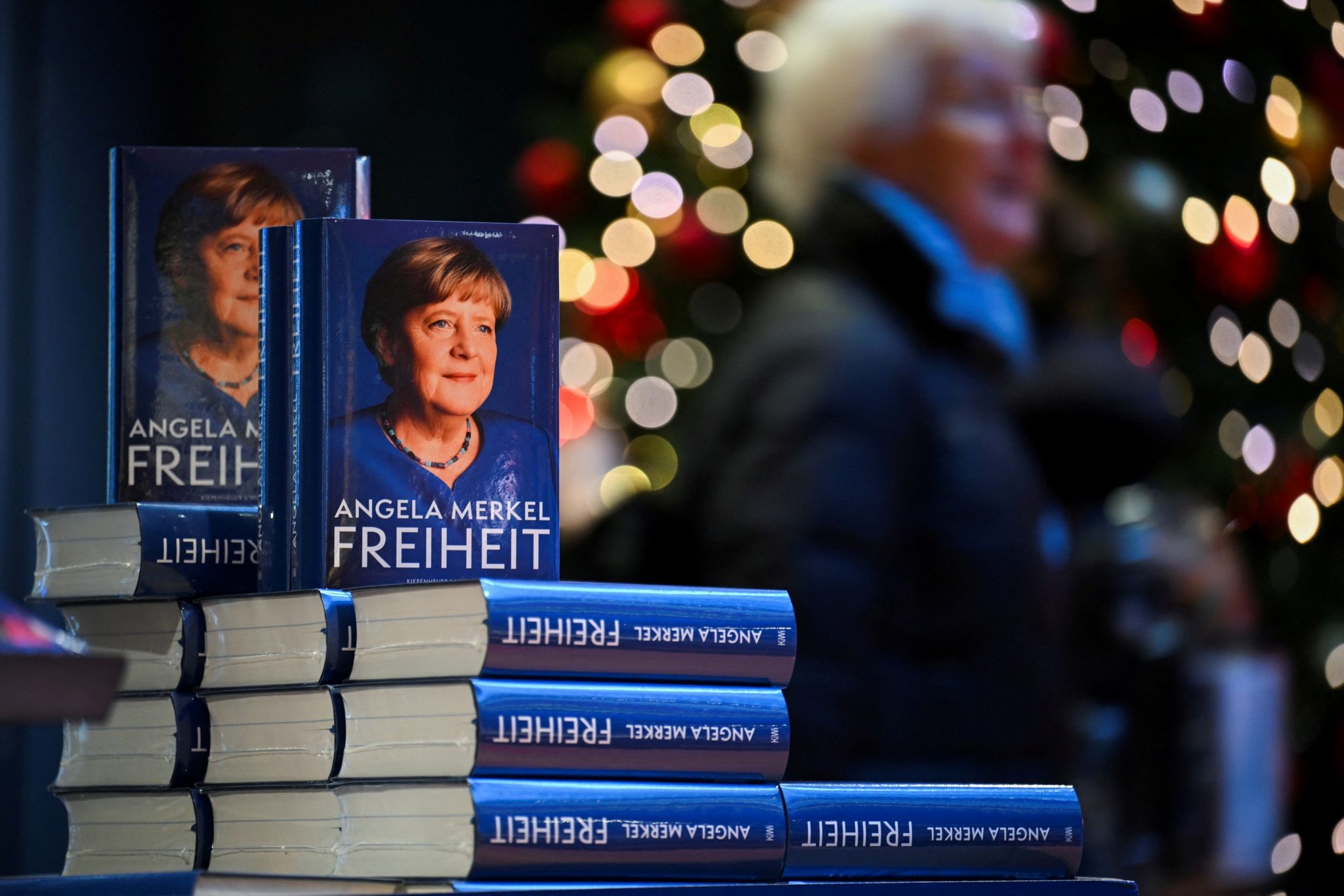

The much-anticipated memoirs of former German Chancellor Angela Merkel were eagerly scrutinized by Greek media on Tuesday, given her written recollections of dealings with the country’s leadership during the turbulent “bailout era” that witnessed the east Mediterranean country flirt with “Grexit” – the ominous portmanteau describing an exit from the eurozone.

Entitled Freiheit (German for Freedom), the autobiography details the tense negotiations and hastened deliberations with Greece’s leadership, and specifically with successive premiers George Papandreou, Antonis Samaras and Alexis Tsipras, with the majority of the recollections regarding Greece focusing on the latter and his decision to call a referendum in July 2015 on creditors’ conditions.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras arrive for a statement at the chancellery in Berlin, Germany, December 16, 2016. REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch

In referring to the first days of the burgeoning Greek fiscal crisis, Merkel writes that she met with then newly elected Prime Minister George Papandreou in the wake of his PASOK party’s landslide victory in October 2009.

According to Merkel, “…at that moment I realized that Papandreou had not yet said anything, so I asked him directly: ‘What do you want, after all?’ The answer was that he didn’t want anything, instead (saying) that Greece was in a very bad situation.”

With the crisis worsening, she said that in early 2010 she again approached Papandreou:

“When will you present your plans to the Commission regarding spending cuts equally four percentage points of GDP?” she writes of her question to Papandreou.

“This is the priority now, in order to get the message across to the markets that they can trust you again.”

Merkel writes that Papandreou replied that he needed time.

“I could not believe my ears. Amid this suffocating pressure to do something about the situation, he (Papandreou) acted as if he had all the time in the world. We were talking in a heated tone, and at the same time, we were speaking in English, French and German. The interpreters barely had time to whisper the words in our ears.”

Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel and Greece’s Prime Minister Antonis Samaras (R) leave a family photo during a European Union leaders summit meeting to discuss the European Union’s long-term budget in Brussels, February 7, 2013.

Negative quip vis-à-vis Samaras

Fast forward to 2012 and Merkel comments, only sparingly, about the new coalition government headed by Antonis Samaras after twin elections in crisis-battered Greece before jumping ahead to January 2015 and the victory of Alexis Tsipras and his leftist SYRIZA party. Tsipras and SYRIZA rode to power on the back of a rabidly anti-bailout and anti-austerity platform that resonated with many Greek voters at the time.

“His (Alexis Tsipras’) victory was due to the anger of many Greek citizens over the bailouts…His predecessor, Antonis Samaras, had failed to fully implement the reforms agreed upon in the second bailout program,” the former chancellor writes, in reference to the fellow center-right politician, Samaras, who also belonged to the European People’s Party (EPP) grouping in Europe.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (L) arrive for a statement at the chancellery in Berlin, Germany, December 16, 2016. REUTERS/Fabrizio Bensch.

Stepped up contacts with Tsipras

Merkel’s references to the Greek bailout crisis dramatically pick after her first meeting with Tsipras in Berlin on March 23, 2015.

“I was anxious, I confess, to see what kind of personality I would have the opportunity to get to know better. He was 20 years younger than me. By that time, we had spoken twice on the phone, with interpreters, and had two brief meetings at European Council meetings in Brussels. He had made a good impression on me then; I could not say more. I knew from our first meetings that he spoke English well,” Merkel writes.

She adds that as she was waiting for Tsipras at the entrance of the federal chancellery to receive him with military honors, the latter’s arrival was delayed because “…he found it necessary to get out of the car in front of the chancellery and personally greet the protestors of the Die Linke party. The cries of ‘Long live international solidarity!’ reached my ears from afar. I only hoped that his stay there would not last long enough to overshadow the atmosphere of his visit, before it even began.

“Tsipras did, indeed, arrive shortly thereafter and got out of the car with a friendly, disarming smile. I greeted him and made a brief remark about his pre-emptive itinerary. He replied confidently and conciliatory, saying no one should never forget one’s followers. I agreed with a smile. Countless photographers turned their lenses on us. We were under close watch,” Merkel writes.

Volition for Greece to remain in eurozone

In revealing her discussion with Tsipras, she said “I stressed to him my firm volition for Greece to remain in the eurozone, something that required work by both of us. Already in the summer of 2012 I had given a great deal of thought to the arguments of those who wanted to convince Greece to leave the eurozone. They failed to persuade me. Since then, my position had been clear. Greece had to remain as a part of the eurozone. Forcing a country to leave the monetary union could have unforeseen consequences. Moreover, once a country left, the pressure on the next (country facing trouble) would increase. Additionally, the euro was more than just a currency and Greece was the cradle of democracy. Nevertheless, I pointed out to Tsipras that there were conditions attached to his country remaining in the euro.”

The lead-up to the referendum

In referring to the controversial referendum called by Tsipras for early July 2015, Merkel said she was deeply surprised.

“In fact, at the June 26 Summit, when all the time had run out, (European Council president) Donald Tusk presented a specific proposal. It was the proposal that the three institutions had almost imposed in the previous days during the summit negotiations with the participation of the Greek Prime Minister, A. Tsipras, but also of (EU Commission President Jean-Claude) Juncker, (IMF Managing Director Christine) Lagarde and (ECB President Mario) Draghi,” she recalls.

Merkel writes that after Tusk’s presentation of the proposal, Tsipras discreetly avoided making a statement, so that his affirmation of the agreement would not be recorded in the Council minutes.

Merkel records the subsequent exchange that occurred:

“Alexis, you haven’t said anything yet. Are you going to speak? ‘No, Donald has already explained everything’,” he replied.

“And what do you intend to do now?” Merkel asks, expressing her surprise.

“I’ll get on a plane to Athens right away and confer with my Cabinet on what we’ll do.”

“I was left with my mouth wide open. I went around the table and approached (French President Francoise) Hollande. He, too, was surprised. Both of us, like the others, had clearly got the impression that Tsipras had accepted the outcome of the night’s negotiations. Tusk had also spoken along the same lines. I went back to Tsipras and asked him: ‘And what do you imagine will come from these consultations?’ ‘I don’t know’… Tsipras replied. When will you know? I insisted. ‘I will tell you that today, early this evening’.”

“Hollande and I arranged for a three-way telephone conversation. Tsipras told us … that his Cabinet had decided to hold a referendum on the agreed program… that on such an important issue, it was up to the people to decide. He was going to announce it to his citizens in a televised address that evening. So far, so good, I thought. Then I asked what his government’s recommendation to the people would be. ‘No, of course,’ he said matter-of-factly. Of all the phone calls I have ever made in my political career, this one probably came as the biggest surprise. For a moment, Hollande and I were speechless.”

“Even more so, when in the final negotiations Alexis Tsipras had brought with him some serious experts, resulting in an agreement that included robust EU funding and loan repayment over a longer horizon.”

‘Greece was now saved’

“…at the July 12 summit everything was different. Things had gotten serious for good; Tsipras had picked banking experts to be in his delegation. The referendum was now a thing of the past. In the morning, we agreed on the main points of a third bailout program financed by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). To facilitate the detailed negotiations on this program in the coming days, the European Commission granted Greece a ‘bridge loan’. On Aug. 19, 2015, the Bundestag voted in favor of the new Greek program.”

“With the program adopted, Greece was now saved,” Merkel underlines in her book, closing out her recollections on the Greek bailout era with an official visit to Athens in January 2019 for a last meeting with Tsipras before he and his SYRIZA party were defeated in the June 2015 general election.

Source: tovima.com

Latest News

Airbnb: Greece’s Short-Term Rentals Dip in March Amid Easter Shift

Data from analytics firm AirDNA shows that average occupancy for short-term rentals dropped to 45% in March, down from 49% the same month last year.

Easter Week in Greece: Holy Friday in Orthodoxy Today

At the Vespers service on Friday evening the image of Christ is removed from the Cross and wrapped in a white cloth

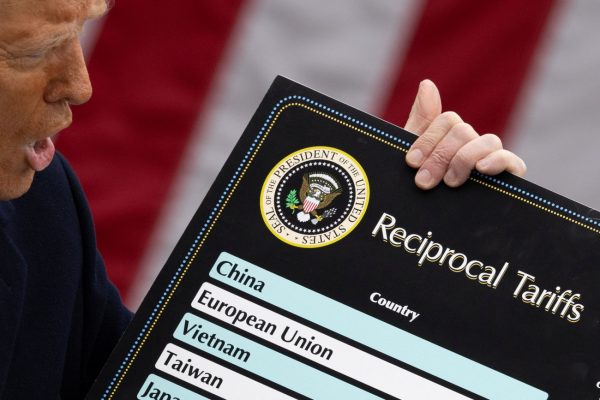

Meloni and Trump Meet in Washington, Vow to Strengthen Western Ties

“I am 100% sure there will be no problems reaching a deal on tariffs with the EU—none whatsoever,” Trump stressed.

ECB Cuts Interest Rates by 25 Basis Points in Expected Move

The ECB’s Governing Council opted to lower the deposit facility rate—the benchmark for signaling monetary policy direction—citing an updated assessment of inflation prospects, the dynamics of underlying inflation, and the strength of monetary policy transmission.

Current Account Deficit Fell by €573.2ml Feb. 2025: BoG

The improvement of Greece’s current account was mainly attributed to a more robust balance of goods and, to a lesser extent, an improved primary income account

Hellenic Food Authority Issues Food Safety Tips for Easter

Food safety tips on how to make sure your lamb has been properly inspected and your eggs stay fresh.

Greek Kiwifruit Exports Smash 200,000-Ton Mark, Setting New Record

According to data by the Association of Greek Fruit, Vegetable and Juice Exporters, Incofruit Hellas, between September 1, 2024, and April 17, 2025, kiwifruit exports increased by 14.2%.

Easter Tourism Boom: Greece Sees 18.3% Surge in Hotel Bookings

Among foreign markets, Israel has emerged as the biggest growth driver, with hotel bookings more than doubling—up 178.5% year-on-year.

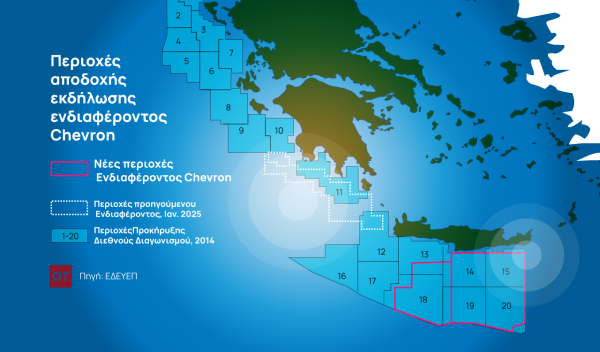

Greece to Launch Fast-Track Tender for Offshore Hydrocarbon Exploration

Last week, Papastavrou signed the acceptance of interest for the two Cretan blocks, while similar decisions regarding the two Ionian Sea blocks were signed by his predecessor

American-Hellenic Chamber of Commerce to Open Washington D.C. Branch

AmCham's new office aims aims to deepen U.S.-Greece economic ties and promote investment and innovation between the two countries

![Πλημμύρες: Σημειώθηκαν σε επίπεδα ρεκόρ στην Ευρώπη το 2024 [γράφημα]](https://www.ot.gr/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/FLOOD_HUNGRY-90x90.jpg)

![Airbnb: Πτωτικά κινήθηκε η ζήτηση τον Μάρτιο – Τι δείχνουν τα στοιχεία [γράφημα]](https://www.ot.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/airbnb-gba8e58468_1280-1-90x90.jpg)

![Airbnb: Πτωτικά κινήθηκε η ζήτηση τον Μάρτιο – Τι δείχνουν τα στοιχεία [γράφημα]](https://www.ot.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/airbnb-gba8e58468_1280-1-600x500.jpg)

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης

Αριθμός Πιστοποίησης